Historical Background

POST CIVIL WAR

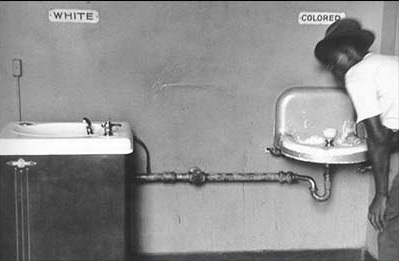

“Separate but equal”

After The Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1863 by Abraham Lincoln, and following the end of the U.S. Civil War won by the North in 1865, the newly freed African-American community had a new future ahead, with both new opportunities and new obstacles. By the 20th Century many strides were made in the African American Community, with many great leaders advocating on behalf of blacks. Advancements were made in the fields of science, literature and business, and yet blacks still had to live in a society that believed in the legal doctrine of separate but equal. The American Civil War (1861—1865) resulted in the cessation of legal slavery in the U.S; however, it did not end overt discrimination directed at African Americans.

Before the end of the war, the Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act (Morrill Act of 1862) was passed to provide for federal funding of higher education by each state with the details left to the state legislatures. Following the war, the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution guaranteed equal protection under the law to all citizens, and Congress established the Freedmen’s Bureau to assist the integration of former slaves into Southern society. After the end of Reconstruction in 1877, former slave-holding states enacted various laws to undermine the equal treatment of African Americans, although the 14th Amendment as well as federal Civil Rights laws enacted during reconstruction were meant to guarantee it. However Southern states contended that the requirement of equality could be met in a manner that kept the races separate. Furthermore, the state and federal courts tended to reject the pleas by African Americans that their 14th Amendment rights were violated, arguing that the 14th Amendment applied only to federal, not state, citizenship.

After the end of Reconstruction, the federal government adopted a general policy of leaving racial segregation up to the individual states. One example of this policy was the second Morrill Act (Morrill Act of 1890), which implicitly accepted the legal concept of separate but equal for the 17 states which had institutionalized segregation. Provided: That no money shall be paid out under this act to any State or Territory for the support and maintenance of a college where a distinction of race or color is made in the admission of students, but the establishment and maintenance of such colleges separately for white and colored students shall be held to be a compliance with the provisions of this act if the funds received in such State or Territory be equitably divided as hereinafter set forth.

Prior to the Second Morrill Act, 17 states excluded blacks from access to the land grant colleges without providing similar educational opportunities. In response to the Second Morrill Act, 17 states established separate land grant colleges for blacks that are now referred to as public historically black colleges (HBCUs). In fact, some states adopted laws prohibiting schools from educating blacks and whites together, even if a school was willing to do so. (The Constitutionality of such laws was upheld in Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U.S. 45 (1908).) Under the ‘separate but equal doctrine’, blacks were entitled to receive the same public services and accommodations such as schools, bathrooms, and water fountains, but states were allowed to maintain different facilities for the two groups.

The U.S. Supreme Court in the 1896 case of Plessy v. Ferguson upheld the legitimacy of such laws under the 14th Amendment, The Plessy doctrine was extended to the public schools in Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education, (1899). Although the Constitutional doctrine required equality, the facilities and social services offered to African-Americans were of lower quality than those offered to whites; for example, many African American schools received less public funding per student than nearby white schools.

Early 1900s

We begin the 20th Century with the U.S. Census of 1900 reporting the population standing at 75,994,575, with 11.6 percent being African American, 8,833,994 black people spreading across the 124-year-old America. African Americans who lived in the South were faced with racism and inequality. With 90 percent of African-Americans living in the South statistically, a shift began to be seen, with 25 percent of African Americans moving to the Northeastern and Midwestern parts. By 1910 that number had doubled, with the African American populations in cities like Chicago, Detroit, New York City, and Cleveland growing by about 40 percent. This event was recorded as the Great Migration occurring between 1910-1930; with a record number 1.6 Million African Americans migrating from the racially segregated south to the more liberal North.

At the beginning of the 20th Century, the African American culture was making much progress in several fields in the world. In January of 1900 James Weldon Johnson wrote the lyrics and his brother John Rosamond Johnson composed the music for Lift Every Voice and Sing in their hometown of Jacksonville, Florida in celebration of the birthday of Abraham Lincoln. The song was eventually adopted as the Black National Anthem. On August 23, 1900, the National Negro Business League was founded in Boston by Booker T. Washington to promote business enterprise. An estimated 30,000 black teachers had been trained since the end of the U.S. Civil War in 1865 and were a major factor in helping more than half the black population achieve literacy by this date.

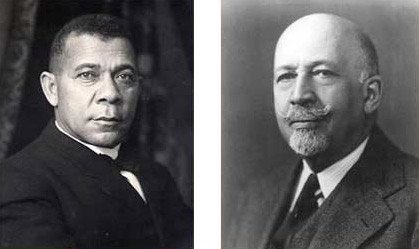

Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois

At the start of the 20th Century, the world begin to see many black leaders and activists. Two widely know leaders at the time were Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois. Booker T. Washington, founder of the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama and originally titled the Tuskegee Normal School for Colored Teachers, founded the school after feeling there were no educational opportunities in the South. He toured the country spreading his idea that African-Americans should accept the terms but work their hardest even with the restrictions blacks faced. Washington had many important friends ranging from Former Presidents William Howard Taft and Theodore Roosevelt. These relationships led to Washington being the first African-American to have dinner in the White House in 1901.

The race riots of the early 1900s led to the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) by W.E.B DuBois in New York City on February 12th, 1909. The NAACP provided critical institutional support and leadership in the fight against racial inequalities in America. Although sometimes criticized as too moderate or bureaucratic in nature, the NAACP’s repeated legal campaign eventually overturned the infamous 1896 Supreme Court ruling sanctioning segregation (Plessy v. Ferguson) and is still a significant political organization to this day.

The race riots of the early 1900s led to the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) by W.E.B DuBois in New York City on February 12th, 1909. The NAACP provided critical institutional support and leadership in the fight against racial inequalities in America. Although sometimes criticized as too moderate or bureaucratic in nature, the NAACP’s repeated legal campaign eventually overturned the infamous 1896 Supreme Court ruling sanctioning segregation (Plessy v. Ferguson) and is still a significant political organization to this day.

Men were not the only new leaders emerging many African-American women were making their mark during the early 1900s. Madame C.J. Walke of Denver became the first African-American woman to be a self-made millionaire by developing and marketing her hair straightening method, creating one of the most successful cosmetics firms in the nation. Between 1900-1910, African-American women opened several educational institutions, including Bethune-Cookman College opened by Mary McLeod Bethune.

Not all African-Americans supported Washington’s “go slow” idea for the progression of African American; one prominent opponent of the idea was W.E.B Du Bois. Du Bois who was the first African-American to receive a doctorate from Harvard University, believed blacks should fight for racial equality. Writing of what he calls, “the talented tenth,” Du Boise believed that one of ten Blacks would should do extensive and progressive studying in one field and lead the rest of blacks forward in the field.

On April 27, 1903, Du Boise published The Souls of Black Folks, an autobiographical account of Du Boise that spoke of racial inequality and injustices. The book calls for agitation from the black community in regards to their condition in America and was written because of the many race riots that were happening in America. One such incident, the Atlanta Race Riots, lasted from September 22 to September 24, 1906, and resulted in the deaths of between 25 to 40 blacks and 2 whites. The 1906 gubernatorial campaign added fuel to the racial fire, as both Democratic candidates, Hoke Smith and Clark Howell, advocated disenfranchisement of all black voters in their respective newspapers. On September 22, after four alleged sexual attacks on white women by black men were reported in the local white press, a mob of approximately 10,000 white men formed downtown. The mob surged through black Atlanta neighborhoods destroying businesses and assaulting hundreds of black men. The violence became so dangerous that the state militia was called in to take control of the city. Still, some white groups persisted in attacking black neighborhoods, and black men organized to defend their homes and families.

In mid-August 1908, the white population of Springfield, Illinois hastily reacted to reports that a black man had assaulted a white woman in her home. Soon afterwards another instance of an assault by a black man on a white woman was reported. These incidents, coming within hours of each other, and later called the Springfield Race Riots the Sheriff announced had been moved to an undisclosed location, the mob turned its wrath of two other black men, Scott Burton and William Donegan, who were in the area. They were quickly lynched. The mob then vented its fury on the homes of black families in Springfield. After rampaging through the city they extended their violence into small communities outside the city limits. The mob targeted stores that had guns and ammunition. Mob leaders carefully directed the participants to destroy only homes and businesses either owned by blacks or which served black patrons, thus leaving nearby white homes and businesses untouched.

Some Springfield blacks fought back in self-defense. They shot back when fired upon, and the first victim of the lynch mob, Scott Burton, used his shotgun in an attempt to save his life and home. The second victim lynched was an 84-year-old cobbler named William Donegan, whose reputation had been tainted in the eyes of the mob by the fact that he had been married to a white woman for over 30 years.

When the carnage finally ended, six black people were shot and killed, two were lynched and hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of property destroyed. About two thousand black people were driven out of the city of Springfield as a result of the riot.

Though Blacks began the 20th Century with newfound freedom, the decade of 1900-1910 offered a new obstacle for African-Americans. Although they were now free, there was still inequality in many states that had enacted Jim Crow laws, which resulted in blacks being treated as second-class citizens. As the new decade approached, the disenfranchisement of the African Americans would only increase with racially-motivated hate crimes intensifying and segregation laws expanding.

1920s

It’s a new decade: it is now 1920 and the African-American community is still dealing with segregation and animosity from the white community. In 1919, The Ku Klux Klan operated in 27 states. Eighty-three African Americans were lynched during the year; among them a number of returning soldiers still in uniform. The census of 1920 reported that U.S. Population at 105, 710, 620 people, with African-Americans representing 9.9 percent of the population at 10,463,131 people.

During the early portion of the 20th Century, Harlem became home to a growing “Negro” middle class. The district had originally been developed in the 19th Century as an exclusive suburb for the white middle and upper middle classes; its affluent beginnings led to the development of stately houses, grand avenues, and world class amenities such as the Polo Grounds and the Harlem Opera House. During the enormous influx of European immigrants in the late nineteenth century, the once exclusive district was abandoned by the native white middle-class. Harlem became an African-American neighborhood in the early 1900s. In 1910, various African-American realtors and a church group bought a large block along 135th Street and Fifth Avenue. Many more African Americans arrived during the First World War. Due to the war, the migration of laborers from Europe virtually ceased, while the war effort resulted in a massive demand for unskilled industrial labor. The Great Migration brought hundreds of thousands of African Americans to cities like Chicago, Philadelphia, Cleveland, and New York City.

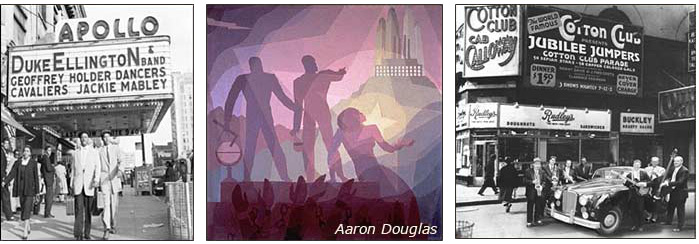

Creativity flourished during the Harlem Renaissance.

The decade of the 1920s witnessed the Harlem Renaissance, a remarkable period of creativity for black writers, poets, and artists, including among others Claude McKay, Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Aaron Douglas, and Zora Neale Hurston. The Harlem Renaissance was successful in that it brought the Black experience clearly within the corpus of American cultural history. Not only through an explosion of culture, but on a sociological level, the legacy of the Harlem Renaissance is that it redefined how America, and the world, viewed the African-American population.

The migration of southern Blacks to the north changed the image of the African-American from rural, undereducated peasants to one of urban, cosmopolitan sophistication. This new identity led to a greater social consciousness, and African-Americans became players on the world stage, expanding intellectual and social contacts internationally. The progress—both symbolic and real—during this period, became a point of reference from which the African-American community gained a spirit of self-determination that provided a growing sense of both Black urbanity and Black militancy as well as a foundation for the community to build upon for the Civil Rights struggles in the 1950s and 1960s.

On August 26, 1920 the 19th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified, giving all women the right to vote. Nonetheless, African American women, like African American men, were denied the franchise in most Southern states.

In June of 1921, Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander of the University of Pennsylvania, Eva B. Dykes of Radcliff, and Georgiana R. Simpson of the University of Chicago become the first African American women to earn Ph.D. degrees.

The Harlem Renaissance, lasting until 1930, brought about great cultural strides: in 1923, Bessie Smith signed with Columbia Records to produce race records. Her recording, “Down-Hearted Blues,” became the first million-selling record by an African American artist. Two years later she recorded “St. Louis Blues” with Louis Armstrong. The same year the Cotton Club opened in Harlem. Women entertainers were subjected to the “paper bag” test: only those whose skin color was lighter than a brown paper bag were hired.

While the North was progressing with a Renaissance, the South still was fighting Jim Crow laws along with the expanding Ku Klux Klan. Record numbers of lynchings throughout the 1920s were recorded: 53 in 1920; 59 in 1921; 51 in 1922. In 1926, in Birmingham, Alabama, women who tried to register to vote were beaten.

During the 20s, African Americans made an impression on American cultural history by telling their story through art, in literature, visual art, theatre, and music. The impact of this explosion of creativity was felt on the international stage and opened many opportunities for African-Americans. Unfortunately, at the end of the decade, the Great Depression affected the entire nation, and many black artists who were relying on patronage could no longer fund their projects.

1930s – 1940s

The Census of 1930 reports growth in the black population with African-Americans representing 9.7 percent of the 122,775,046 people.

In 1931, Nine African American “Scottsboro Boys” (Alabama) were accused of raping two white women and convicted quickly. The trial focused national attention on the legal plight of African Americans in the South. The case went to the United States Supreme Court in 1937, and the lives of the nine were saved, though it was almost twenty years before the last defendant was freed from prison. The trial of the Scottsboro Boys is perhaps one of the proudest moments of American radicalism, in which a mass movement of blacks and whites—led by Communists and radicals—successfully beat the Jim Crow legal system.

In 1932, Franklin Roosevelt was elected President. While in office Roosevelt expanded the Presidential office by enacting The New Deal. This new legislation allowed a lot of government funding for many African Americans. In 1934, the Apollo Theater opened in New York City, which allowed the showcasing of many black entertainers. In 1935, Mary McLeod Bethune formed The National Council Of Negro Women (NCNW) in New York City, with the support of the leaders of 28 of the most notable black women’s organizations. The founder and president until 1949, Mary McLeod Bethune, envisioned a unified force of black women’s groups fighting to improve racial conditions nationally and internationally.

The NCNW focused on gathering information, making credible contacts, and sponsoring educations programs. The most notable effort in the 1930s was the 1938 White House Conference on Governmental Cooperation in the Approach to the Problems of Negro Women and Children. Beginning with this conference, representatives of the NCNW began to regularly visit the White House to call for more black female administrators in upper-level government positions.

In the 1940s the NCNW engaged in a series of activities, including the campaign to desegregate the armed forces, and assisting women globally during War World II. In 1941, the NCNW became a member of the U.S. War Department’s Bureau of Public Relations under the Women’s Interest Section where they lobbied for black women in the U.S. Army. By 1942, The Women’s Army Corps (WAC) accepted African American women, admitting them into the service overseas in the 688th Central Postal Battalion. They also launched education campaigns, urging black workers to improve their job skills and to maintain professional attitudes and appearances. In its concern for minority women around the world, the NCNW advocated U.S. participation in the United Nations.

Crystal Bird Fauset with Eleanor Roosevelt.

In 1938 Crystal Bird Fauset was elected to the Pennsylvania state legislature, representing the 18th District of Philadelphia, which was 66% white at that time. Crystal Bird Fauset became the first African-American women to be elected to state legislature. As a state representative, Fauset introduced nine bills and three amendments on issues concerning improvements in public health, housing for the poor, public relief, and supporting women’s rights in the workplace.

In 1941 Fauset’s friendship with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt helped her secure the position as assistant director and race relations director of the Office of Civil Defense, becoming part of President Roosevelt’s “Black Cabinet” and promoting civil defense planning in black communities, recruitment of blacks in the military, and dealing with complaints about racial discrimination. In 1944, disappointed by the Democratic Party’s failure to advance civil rights, Fauset switched to the Republican Party and later became a member of the Republican National Committee’s division on Negro Affairs.

After World War II Fauset turned her attentions to a more global forum, helping to found the United Nations Council of Philadelphia, which later became the World Affairs Council. Throughout the 1950s she traveled to Africa, India, and the Middle East to meet and support independence leaders. Fauset died on March 27, 1965 in Philadelphia.

The 1930’s decade ended with American entering into World War II with a still-segregated military.

The 1940 census reported the U.S. population at 131,669,275 people, with the African-American population at 12,865,518 representing 9.8 percent of the population.

On February 29th of 1940, Hattie McDaniel became the first African-American to win an Academy Award for her performance in Gone With the Wind.

Tuskegee Airmen

n 1941, the Tuskegee Airmen squadron was created. The Tuskegee Airmen squadron was made up of roughly 450 men who were originally part of the 99th Squadron, ably led by Lt. Col. Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. They eventually became the 332nd Fighter Group and the 477th Bombardment Group Of the U.S. Army, and saw action in North Africa and Italy where they distinguished themselves winning hundreds of decorations for skill and bravery. Flying P-39 Airacobras, P-40 Warhawks, P-47 Thunderbolts and, later, P-51 Mustangs, among their feats was the downing of more that 100 enemy aircraft in aerial combat and the first-ever sinking of a large ship without the use of explosives. The Tuskegee Airmen were the only Army Air Force group not to lose an escorted Allied bomber to an enemy aircraft attack. Moreover, their outstanding performance served to bolster African American pride and facilitated the transition to an integrated military in the post-war years. Among the Tuskegee Airmen emerged a number of future leaders, including San Francisco physician Dr. Wendell Lipscomb and four-star Air Force General Daniel “Chappie” James.

Between 1941-1945: American entered World War II after the surprise military attack by the Japanese on Pearl Harbor on the morning of December 7, 1941 (December 8 in Japan). The Japanese viewed the attack as a preventive action in order to keep the U.S. Pacific Fleet from interfering with military actions the Empire of Japan was planning in Southeast Asia against overseas territories of the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and the United States.

After the United States entered the global conflict, there was a desperate need for factory labor to build the war machine needed to win World War II. This resulted in an unprecedented migration of African Americans from the South to the North and West, which transformed American politics as blacks increasingly voted in their new homes and pressured Congress to protect civil rights throughout the nation. Their activism laid much of the foundation for the national Civil Rights Movement a decade later. In 1948, President Harry S. Truman issued Executive Order 9981 directing the desegregation of the armed forces.

1950s

Brown vs. the Board of Education

As the 1950s approached, the goal was to desegregate the south and overthrow Jim Crow laws in the south. Much of the focus of the 1950s in African-American history revolved around the Civil Rights Movement, lasting from 1955-1968. Many mark the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement as May 17th, 1954, the date of the landmark Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, in which the highest judicial body in the land unanimously agreed that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. The ruling stated, in part: “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” Thus was overturned the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision which had sanctioned “separate but equal” segregation of the races. That ruling paved the way for large-scale desegregation in the United States. The plaintiffs in Brown v. Board of Education were eloquently championed by attorney Thurgood Marshall, who brilliantly argued against “separate but equal” and who later became the first black justice of the Supreme Court.

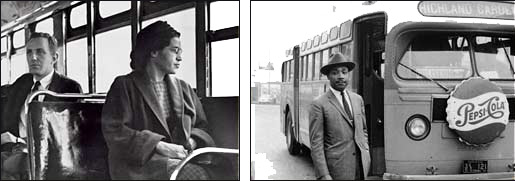

Bus boycott

The next year, 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama, NAACP member Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat at the front of the “colored section” of a bus to a white passenger, defying a southern custom of the time. In response to her arrest, the Montgomery black community launched a bus boycott, lasting for more than a year, and resulting in the desegregation of the buses on Dec. 21, 1956. As newly-elected president of the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., was instrumental in leading the boycott.

In January of 1957, Martin Luther King, Charles K. Steele, and Fred L. Shuttlesworth established the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and King became its first president. The SCLC became a major force in organizing the civil rights movement and based its principles on nonviolence and civil disobedience. According to King, it was essential that the civil rights movement not sink to the level of the racists and hate-mongers who opposed them: “We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline,” he urged. That same year in response to the ruling of the desegregation of schools, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus refused to obey the ruling of integration. President Eisenhower sent federal troops and the National Guard to intervene on behalf of the students, who become known as the “Little Rock Nine.”

Federal troops were ordered in to protect the “Little Rock Nine.”

1960s

Greensboro sit-in to desegregate Woolworth’s

On February 1, 1960, four black college students in Greensboro, North Carolina, demanded service at a Woolworth’s lunch counter. When the staff refused to serve them, they stayed until the store closed. In the following days and weeks this “sit-in” idea spread through the South. At first several hundred—and then several thousand students—participated in protest against this form of segregation.

To support and coordinate this spontaneous movement, Ella Baker, a National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) official, called a conference at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina from April 16 to 18, 1960. It was there that the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was founded. Its first chairman was Nashville college student and political activist Marion Berry.

Although SNCC, or ‘Snick’ as it became known, continued its efforts to desegregate lunch counters through nonviolent confrontations, it had only modest success. In May 1961, SNCC expanded its focus to support local efforts in voter registration as well as public accommodations desegregation. The high point of its efforts came in 1964 with the Mississippi Summer Project which became popularly known as “Freedom Summer.” Hundreds of black and white college student volunteers joined Mississippi SNCC workers and local civil rights activists in a bold campaign to register thousands of black voters across the state for the first time. The effort drew national attention particularly, when three SNCC workers, James E. Chaney of Mississippi, and Michael H. Schwerner and Andrew Goodman of New York, were killed by white supremacists.

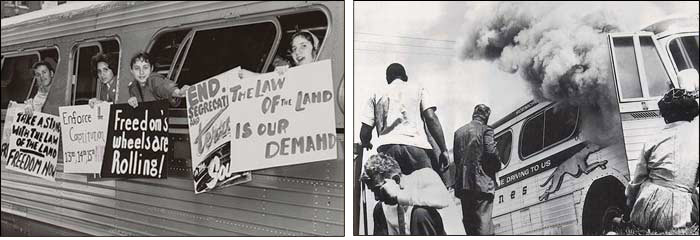

During 1961, SNCC and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) sponsored bus trips by student volunteers through the South to test out new laws that prohibited segregation in interstate travel facilities, which included bus and railway stations. Several of the groups of “freedom riders,” as they are called, were attacked by angry mobs along the way.

During the 1960s there were a number of race riots throughout the US that demonstrated the disparity of justice, the racial inequality, and the deep tensions coming from the some African-American neighborhoods in Chicago (1964), Watts Los Angeles (1965), Detroit (1967), Newark (1967), and Milwaukee 1967.

Freedom Riders braved the threat of mob violence as they worked for desegregation in the South.

There were several key events affecting the Civil Rights Movement during 1963. On April 16th, Martin Luther King was arrested and jailed during anti-segregation protests in Birmingham, Ala. There, he wrote his seminal “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” arguing that individuals have a moral duty to disobey unjust laws.

That May, during civil rights protests in Birmingham, Ala., Commissioner of Public Safety Eugene “Bull” Connor used fire hoses and police dogs against black demonstrators. These images of brutality, which were televised and published widely, were instrumental in gaining sympathy for the civil rights movement around the world.

On June 12th, Mississippi’s NAACP field secretary, 37-year-old Medgar Evers, was murdered outside his home. Byron De La Beckwith was accused and tried twice in 1964 for his murder, but both trials resulted in hung juries. Thirty years later he was convicted of murdering Evers.

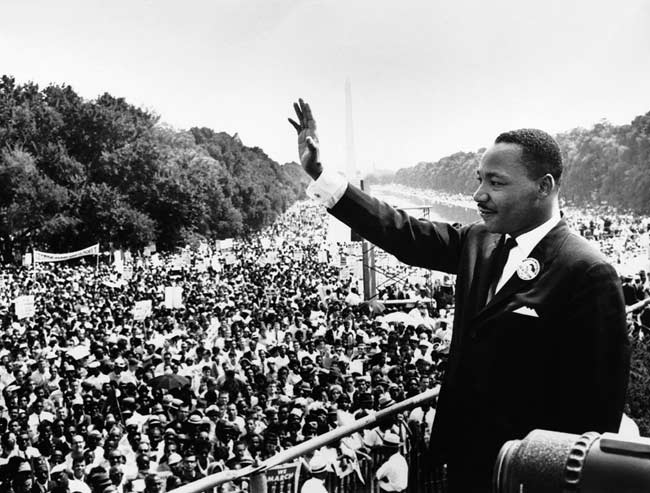

On August 28th, 1963 the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom took place in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963, a milestone in African American history. Attended by some 250,000 people, it was the largest demonstration ever seen in the nation’s capital, and one of the first to have extensive television coverage. Those who were there clustered around the Lincoln Memorial and listened to Martin Luther King deliver his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

March on Washington / I Have a Dream

On September 15th, 1963, four young girls (Denise McNair, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, and Addie Mae Collins) who were attending Sunday School were killed when a bomb exploded at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, a popular location for civil rights meetings. Riots erupted in Birmingham, leading to the deaths of two more black youths.

With the unfair treatment of African-Americans gaining national attention from the Civil Rights Movement, and because of the persistence of leaders like Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, a victory was finally achieved on July 2nd, 1964 when President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The most sweeping civil rights legislation since Reconstruction, the Civil Rights Act prohibited discrimination of all kinds based on race, color, religion, or national origin. The law also provided the federal government with the powers to enforce desegregation.

President Lyndon Johnson signs the Civil Rights Bill of 1964

African Americans were also making great strides in pop culture with music and in films. In music, Barry Gordy had begun Motown in Detroit in 1959, but it was not until the 1960s that Motown Records peaked. From 1961 to 1971, Motown had 110 top 10 hits, with renowned artist like The Supremes, The Jackson 5, and the Four Tops. In 1964, Sidney Poitier became the first African-American male to win for Best Actor at the Academy Awards for his role in Lilies of the Field.

With all the political change happening in favor of blacks, came a lot of unrest within white supremacy groups. The 60s was also a decade of assassinations of political figures. In 1963 Lee Harvey Oswald assassinated President John F. Kennedy while Kennedy was making a public appearance in Dallas, Texas; in 1965, black activist Malcolm X was shot while delivering a speech at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem, New York. On April 4, 1968, in Memphis, TN, James Earl Ray shot and killed Martin Luther King.

1970s

While blacks had spent most of the previous decades in a society where they were deemed inferior with fewer opportunities being presented to them, the new decade of 1970 rang in with many blacks in power. Black nationalism surfaced and gained strength in the many ghettos of America because of the influence of the Black Panther Party. Founded in 1966 and originally called The Black Panther Party for Self Defense, this organization spent most of the 70s engaged in protesting, organizing black people, and fighting poverty within the black community.

The Panthers abandoned the ideals of peaceful protesting that leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. had worked so hard to implement during the 1960s. The Panthers had several stand-offs with police, and at a rally in New York City in 1968, spoke their goals aloud: “We want to become masters of our own destiny…we want to build a black nation to benefit black people…The white people who killed Bobby Hutton are the same white people sitting here.” In 1968, the group shortened its name to the Black Panther Party and sought to focus directly on political action. Members were encouraged to carry guns and to defend themselves against violence. An influx of college students joined the group, which had originally consisted chiefly of “brothers off the block.” This created some tension in the group. Some members were more interested in supporting the Panthers’ social programs, while others wanted to maintain their “street mentality.” For many Panthers, the group was little more than a type of gang.

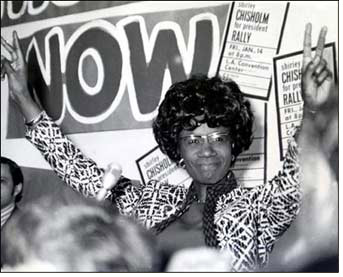

Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman elected to the US Senate.

The 70s brought about a new role for black women, with the first black woman, Shirley Chisholm, being elected to the U.S. Senate. A Brooklyn-born Democrat, she also became the first black woman to a make a bid for the U.S. Presidency in 1972. Chisholm stated she ran for office because, “in spite of hopeless odds… to demonstrate the sheer will and refusal to accept the status quo.” In addition, Chisholm survived three assassination attempts during her campaign. She later went on to do a lot of legislative work for poor, inner city inhabitants.

White feminists of the 1970s now had a new alliance with black feminists (who felt their needs had been left out of the feminist movement). Black women started rising to the occasion. Toni Morrison became the first African-American woman to win a Nobel Prize for Literature; Angela Davis, a famed activist and professor (who was charged and acquitted with the murder and kidnap of a California judge during the 1970s) would go on to become a professor at the University of California-Davis and write about feminism and the early Black Blues singers. After extensive research, she concluded that the tales of woe in those songs were not stories of victims, but rather women of strength, who were the first to name the pain in music.

Black women now had a new role in America: she was no longer just “the Help”—she was now the voice for many struggling African Americans. Black women were breaking down doors and reaching new heights. During the late 70s and early 80s, Tina Turner separated from abusive husband Ike Turner and began her own journey. She went from singing the funk-inspired music her husband forced upon her, to joining the ranks of Rod Stewart, Bruce Springsteen (etc), and became a rock legend. Turner has gone on to sell over 180 million records, have a New York Times best-selling biography that was turned into an Academy Award-nominated film, create a distinguishable career, and inspire many current artists today, such as Beyoncé and Rihanna.

The old sound of doo-wop and the big band sound that Barry Gordy had spent so many year building as the black sound (with such groups as the Supremes and Martha and the Vandellas,) was now being replaced with big voices recorded over heavy dance beat. The sound was known as disco, the sound coming from Europe that had become all the rage in the United States with artists like Patti LaBelle and the LaBelles recording iconic songs such as Lady Marmalade, and the rise of Donna Summer recordings such as Hot Stuff and Bad Girls. This created a new sound for the African American women, where she was seen as a sex symbol. The African American women were viewed as artists, creating a sound that would become the foreground what we know as modern R&B.

With the jobless rates down, post-Civil Rights America ensured the growth of African Americans, with many blacks working and growing in managerial positions.

1980s

Once the 1980s arrived and a new Presidential Administration took over, things would soon change. Ronald Reagan became the 40th President of the United States, with intentions to bring back a pure America and protect America from Communism abroad. The United States of American became involved in what is known as the Cold War. While the Cold War was never fought on ground, it was an arms races against the former Soviet Union, in which both countries tried to “out buy” the other country in weapons. In order to participate in this war, Ronald Reagan cut several domestic policies to help fund the Cold War against the Former Soviet Union. His economic policy is commonly referred to as “Reaganomics.”

The following items speak volumes as to his position on equal opportunity.

- Supported racism with remarks like those that characterized poor, black women as “welfare queens.”

- Fired U.S. Commission on Civil Rights members who were critical of his civil rights policies, including his strong opposition to affirmative action programs.

- One of the commissioners, Mary Frances Berry, who now chairs the Commission, recalls that the judge who overturned the dismissal did so because “you can’t fire a watchdog for biting.”

- Sought to limit and gut the Voting Rights Act.

- Slashed important programs like the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) that provided needed assistance to black people.

- Appointed people like Clarence Thomas, who later became a horrible Supreme Court Justice, to the Equal Opportunity Commission; William Bradford Reynolds, as assistant attorney general for civil rights; and others who implemented policies that hurt black people.

- Doubted the integrity of civil rights leaders, saying, “Sometimes I wonder if they really mean what they say, because some of those leaders are doing very well leading organizations based on keeping alive the feeling that they’re victims of prejudice.”

- Tried to get a tax exemption for Bob Jones University, which was then a segregated college in South Carolina .

- Defended former Sen. Jesse Helms’ “sincerity” when that arch villain of black interest questioned Martin Luther King’s loyalty.

- The federal budget during the Reagan years tells the tale in stark, dollar terms. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, as reported by the Los Angeles Times as Reagan left office in 1989, programs that helped black America suffered greatly during his tenure. During Reagan’s tenure the black middle class suffered due to taxing the poor and giving tax cuts to the rich. Reagan cut a lot of government-funded, social programs that a lot of blacks relied on.

What lies ahead?

At the present time, issues of importance for African-American include structural barriers to jobs and equality, disproportionate numbers of African-American men in prison–called by some as the “Modern Jim Crow,” rising income disparity between Blacks and Whites, housing crisis with people losing their homes, high unemployment—especially for young Black males, and so on.

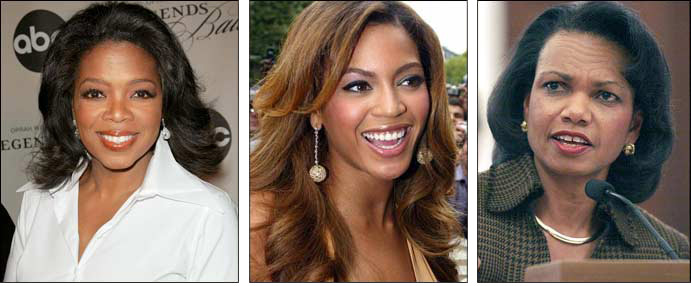

Oprah Winfree – Beyoncé – Condoleezza Rice

We had eight years (2008 to 2016) where African-Americans lived in a world full of opportunities, and were not limited by many obstacles. Then, little black girls found inspiration in First Lady Michelle Obama, from Oprah Winfrey, the first African American woman to have an internationally syndicated talk show that ran for three decades, and one of the few female, black billionaires. Little black boys can look to President Barack Obama, the 44th President and the first African American elected to the office of the Presidency.

Barack Obama, the 44th President of the United States.

Little girls can still look to Beyoncé, an African-American woman who sings about woman empowerment and who has sold more that 250 million records. The highest generating genre of music today is R&B and Rap, which is dominated by black artists such as Jay-Z, Kanye West and Beyoncé, who sell out venues throughout the globe. For inspiration, little boys can look to John Legend, Snoop Dog, and Drake, who play all over the world.

Again, in the political arena, Condoleezza Rice was appointed US Secretary of State (first black women to hold this title) with the white-male dominated Republican Party. Maya Angelou was one of the most recognized voices of our time—a celebrated poet writing about the perils of the past of African-American ancestors, a novelist and educator, a producer and activist. Suzan Lori Park recently revised the African American classic, Porgy and Bess, writing historical themes while creating new techniques and genre to tell the African-American journey. In addition, there are amazing African-American performers on the stage, bringing down the house. Those include 5-time Tony winner Audra McDonald, as well as Cynthis Erivo, Marisha Wallace, Vanessa Williams, Courtney Reed, LaChanze, and Carrie Compere. Both Williams and Compere were featured as performers in SISTAS several years ago.

Today we find two goals: One, not to unite just blacks and preserve a culture, but rather to integrate all (white, black, Asian, Indian, etc.) into the culture of multi-cultural American history; to make it all “American” history. Embracing and appreciating the differences of the various ethnic and racial groups does not lead, as Schlesinger suggested, to the “disuniting of America,” but rather (as current scholars suggest), to the “re-uniting of America.”

There is another group working towards separation of the races and reducing voting rights. It is important to vote and choose which political candidates stand for what you believe in.